I have just participated on a podcast where we talked about translation as one of the most positive applications of AI. What AI chatbots offer today is already amazing, but imagine when thanks to an earpiece - or a nano chip under your skin, who knows! - you can have a fluent conversation with somebody who speaks a completely different language while both of you sit on a terrace under the sun! A dream come true for most. Except for interpreters and translators, for whom this probably feels more like a nightmare.

As I was half asleep on the train this morning, I couldn’t help but feel something nagging me about this world in which, without having learned Esperanto, we are still able to understand each other (or rather, understand what the other one is saying, which is not the same). And thinking about this AI Babel Tower brought me to the day I was walking with my daughter around Mikonos, in Greece, on a hot day of the summer when she had just turned three.

A little pause during our walk to give you context.

My husband and I speak English to each other because he is French, I am Spanish, and when we met in the US this was the only common language we could speak. That has changed since, but English stuck - I am very stubborn that way, and it is very difficult to change once I’ve established a relationship in a certain language. Anyway, when my daughter was born, as we were living in Spain and she would learn Spanish anyway1, we decided I would speak to her in English, her dad would do it in French and that’s how she grew up trilingual.

Back to the walk.

She looked at the typical Mykonos windmills on top of a hill and asked: “Mom, what is that”? As I normally did whenever we discovered new words, I said: “Those are windmills”, and I went on to explain the mechanism of a windmill as best as I could. I was about to venture into how Don Quixote thought they were giants when she exclaimed: “Ah, you mean moulins!2!”. I was impressed. “WOW!” - I thought - “I can now use the word in another language to explain things. This is going to be so much easier!”. But I also felt something was lost when I gained that new power. I somehow valued how talking to her forced me to try explaining words I had never had to define before.

I have very much enjoyed learning and speaking (or trying to speak) different languages. I remember the magic of those conversations as a teenager where you could go on for half an hour of laughs, broken sentences, and the helpful international language of gestures, simply trying to explain something to a friend that would have taken three minutes if we both spoke the same language. And I appreciate how language is such a great excuse to explore nuances. At home, we often have fascinating conversations triggered by some particular word. Let’s say we are speaking English, for example, and my husband wants to express something he can only exactly describe with a French word. This may lead us to what would be the closest way to say that in English, or whether there is a similar word in Spanish or Gallego. And if there is not, we may wonder why. And we may end up talking about history, or a local saying that my grandma used to say…

Ok, not every day at home is that idyllic, I confess. But we don’t have a TV and that may help some of these conversations happen.

Could it be that the reason why I am slightly uncomfortable with the AI Babel Tower is simply that this magic that comes from learning multiple languages would eventually be lost? That is surely part of it, but there is also something that concerns me about the generative AI approach to translation and how it may affect, especially, minority languages.

Multiple initiatives have been launched worldwide to train general-purpose models focused on languages other than English, with governments investing considerable amounts of money to build models like the “Spanish GPT”3, for example. Is this the type of investment needed to ensure minority languages continue to thrive? I understand the need for tech sovereignty but, is language part of it? What about the other 7000 or more languages in the world? Do they need to invest in their local language-trained models to survive?

Let me ramble a bit while I think about these questions…

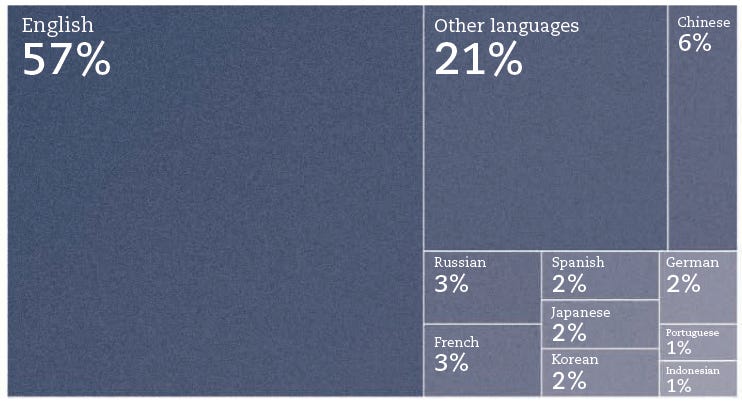

I have never felt that learning a new language took anything away from my native ones (I grew up with two, Gallego and Castilian, which is what outside of Spain you’d call Spanish). It’s just like people tell me I would feel if I had more kids: when you only have one you think you can never love anyone else as much. When you have another, you realize you can. The kids analogy still holds when, as I write in English I think my Spanish may be feeling neglected, as if I went to the park with one kid and left the other one at home. That is why I was surprised by the slight pinch I felt in… my pride maybe? … when I saw this OECD report4 showing that only 2% of the open-source datasets used to train Gen AI models in 2024 were in Spanish.

This was not a mother-like reaction! The kid’s metaphor may not be a great one after all, unless parents can have favourites (another thing I have not experienced having an only child). After that first emotional reaction, though, the more rational one kicked in. English is the de-facto global language online, and as AI has been trained with available online content, it is not surprising the majority of the training data is in English.

My experience is that when you converse today with the latest general-purpose models trained on mostly English content, you do have more coherent responses if you interact in English, but you can still speak to a model in Gallego (and over 100 other languages), and get more or less fluent responses. It’s like talking to somebody who is not completely fluent in the language, and it will have a lot of references in English if it cannot find the exact word. A bit like when I speak “Portuñol”, splashing Spanish words here and there when I don’t know or remember the Portuguese one.

If you want the alternative, you need lots of training data in the language in question. And when you want fluency in a minority language like, let’s say Gallego, where do you get so much general data? I am afraid the easiest way would be to take content that was originally in other languages (and most of the content on the internet is already in English), use AI to translate it to Gallego, and then use the AI-translated content for training. This should teach the model to speak better words in Gallego, yes. But would it not be a different Gallego? One where all those cultural nuances that made Gallego what it is today may be lost? I am afraid we could lose even more than I did in Mikonos!

I can’t help but wonder how much of what drives these “local language model” initiatives is an emotional reaction (a slight pinch in our pride?), and whether these minority languages would be better off if we stopped making such a big deal about general-purpose5 models having to be fluent in them. As a bonus, people would continue to have an incentive to learn at least another language.

And maybe, just maybe, this would bring us a little bit closer to understanding each other and not simply understanding each other's words.

I read while I was pregnant that when you live in a country you learn the language by “absorption”, even if it is not the language you speak at home. It has been proven in my daughter’s case, and maybe I will someday tell you a funny story about how much she “absorbed”.

“Moulins” is the word for windmills in French.

The Spanish government, for example, has invested €1.5 billion: https://alia.gob.es/eng/

https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/2024/05/oecd-digital-economy-outlook-2024-volume-1_d30a04c9.html

Please note that I am talking about general-purpose models, like ChatGPT. Models that are focused on specific tasks may not have this problem, as there may be enough data (not necessarily public) for in the language in question.

I truly appreciate your perspective. It evoked a sense of sadness and made me reflect on what might be at stake here. Growing up and living in several countries myself I always dreamt of an easy way to communicate in different languages. But I guess what’s easy isn’t always the best!